Narrated by Ájahi, Kuikuro people, circa 1960

Reworked by Javier Taboada after Bruna Franchetto & Carlos Fausto translation from the Kuikuro

* * * * * *

“I’m going there

walking a little,” she said to her children

then the two women went away

& when the Widow & the Mother-in-law were not so far from the village

they left them

& her children screamed:

“STAY HERE!”

& some said

the Mother-in-law put the Widow in front of herself

& she moved her up

& she moved her up

& she moved her up

on this side

ihhh

they reached almost to the limits of heaven & earth

and there they stayed

they walked up

“well turn your face down

ah”

said the Mother-in-law

“turn your face down!

the face turned down

upside down”

& the Earth appeared upside down

the way down from the sky to above

here

here

above our Earth

then they went away

they stayed right at the beginning

of the main path of the dead

the Mother-in-law brought the Widow

right to the edge of the path

& she erased the Widow’s footprints

so the dead

could not see her footprints

…

they stayed there

at the back of the houses of the dead

& entered a house

directly

over the platform

among the pieces of dried cassava paste

there was a lot of cassava flour stored there

there was a lot of the food

of the dead

the food of the dead

& the Mother-in-law

was sweeping

& the Mother-in-law

was making her unknown

so nobody knew

so nobody knew

& then

“bring me a túhagu”

a dead woman was saying

the dead woman next door said

“LISTEN!”

said the Mother-in-law

“LISTEN!”

“they are trying to speak

those which were our words

& that’s how those which were our words

are here

they were trying to speak

those which were our words”

shortly after she heard:

“bring my igihitolo”’

“LISTEN TO THIS!

“that dead woman refers to the alato

which is the name for a griddle

to cook cassava bread

in the words of the living

but before she has said

‘bring me a túhagu!’

referring to the strainer in which she used to sift for herself

instead of saying angagi

as the living call it

& that’s why

to cook cassava bread

she has said ‘bring my igiholoto’”

“LISTEN!” she said

“this is what those which were our words

are like here”

said the Mother-in-law

“those which were our words were reversed”

COMMENTARY

source. Bruna Franchetto, Carlos Fausto, Ájahi Kuikuro & Jamalui Kuikuro, Mehinaku

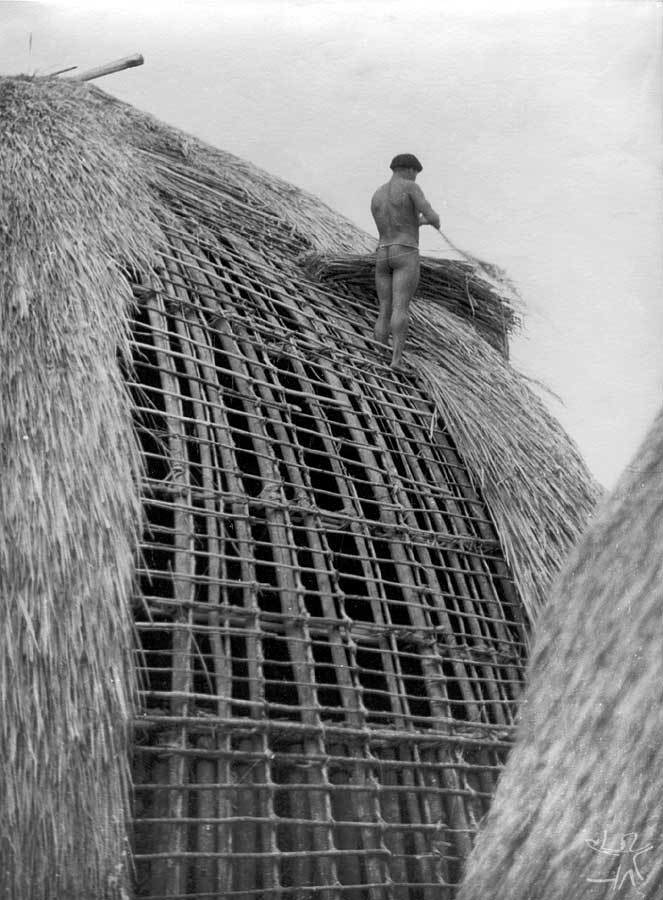

Kuikuro, In Kristine Stenzel & Bruna Franchetto (eds.), On this and other worlds: Voices from Amazonia, pp. 23–87. Berlin: Language Science Press, 2017.Anha ituna tütenhüpe itaõ, “The woman who went to the village of the dead”, is a story recorded by Bruna Franchetto & Carlos Fausto in 2004, in Ipatse, the main Kuikuro village, close to the Xingu River in Southern Amazonia, where the Kuikuro people have lived since, at least, the 16th century.

The storyteller was a woman named Ájahi, a renowned ritual specialist and expert singer. Franchetto & Fausto wrote about the story-telling: “In Ájahi’s version, a woman is taken by her dead mother-in-law and by her longing for her dead husband, through the path of the dead (anha) to their celestial village.

“In the afterworld, other words are used, referring to an inside-out world. The text recurrently makes use of the suffix –pe, as in kakisükope, which can be loosely translated as ‘our former words’ or ‘those which were our words’, referring to the words of the living that the dead seek out and transform, in their language of the dead, into other words. … Ájahi insists on the contrast/complementarity between the language of the dead and the language of the living. The suffix -pe here means that the dead are trying to recover their language (that they used when they were alive), but in this effort they only find synonyms in the language of the dead.”

No comments:

Post a Comment