Transcreated by Matthew Rothenberg & Javier Taboada from a Spanish/Quechua translation by Jesús Lara

is it true

my sweet dove

that you’re flying away

to a far distant land

& you’ll never come back?

then who's gonna remain

in your poor empty nest?

in my sadness & pain

to whom should I run?

just show me the road

that you're rambling on down

I’ll get there before you

& wet the hard ground

with my tears where you’re walkin’

& there on that road

with the sun beating down

my breath is a cloud

& the cool of its shadow

comes down like a gift

when you feel the bite

of the fiery thirst

my howls will rain down

you'll have sap to drink

will you rocky creature

with your heart of stone

leave me all alone?

the sun has gone out

my baby has gone

I walk & no one

will have mercy on me

none at all

my dove you were young

& you blinded me then

as if I was looking

straight into the sun

your eyes falling stars

I’m soaked in their glow

& like the night's flash

they twisted my path

I’ll borrow the power

of an eagle’s wings

to see you again

with the winds in my arms

I'll give them to you

our lives are entwined

in such a strong bond

that even death

can't split us apart

we believed that forever

we’d be one and the same

dove

you always knew how

to chase off my pain

wherever I'll be

as long as I live

you'll be the dawn

that breaks in my heart

& every time that Mount Misti lights up

remember me

‘cause I’m thinking of you

& to reach where your love is

how far must it travel --

my widower’s heart?

COMMENTARY

source: Signo, Cuadernos Bolivianos de Cultura, 41, 1994.

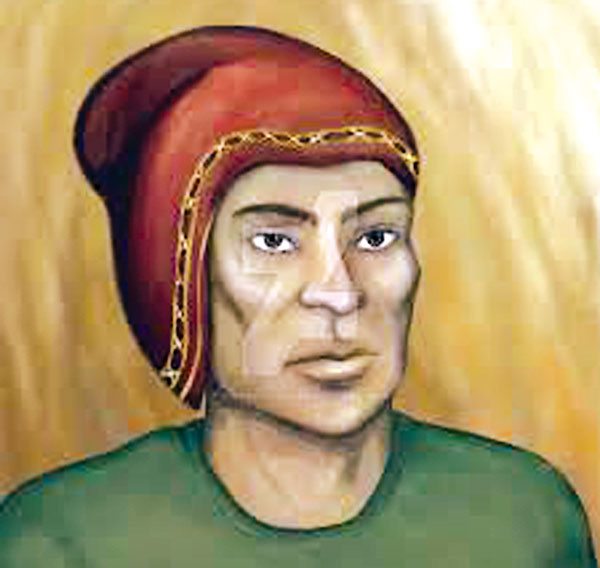

(1) Sylvia Nagy -- in the source just cited -- writes about the importance of Juan Wallparrimachi: “The arrival of the Europeans to the Tawantinsuyu [literally ‘The Four Divisions,’ i.e. the Incan empire in Quechua language] and their continuous presence since then has produced irreversible changes in the character of the natives and in their literary expression. Pre-Columbian poetry showed a great variety of genres ... Some works in Quechua -- during colonial times -- survived anonymously: Ollanta, Ushka Páukar and Mánchay Puitu. Folklore absorbed and safeguarded the poems of many, without registering or remembering their names. The only exception is the case of Juan Wallparrimachi, a 17th-century Bolivian poet, who wrote in Quechua.”

(2) Juan Wallparrimachi was a poet & revolutionary during Bolivia’s independence movement. The legend says that he never used any weapon aside from the Incan slingshot. On August 7th, 1814, Wallparrimachi died in battle against the Spaniards. He was twenty years old. Although he developed new poetical expressions -- from the merging of his own poetical tradition with Spanish forms (one of the outcomes, for instance, is his appropriation of the ten-line décima & the way he infused it with Quechua imagery & language), his works were -- & still are – too often overlooked by literary scholars.

No comments:

Post a Comment