Picking the last wild flower

Standing on the edge of a heather moor where the Pentland Hills rise is a whinstone boulder with a single vein of quartz. This stone is a poem. Inscribed ‘CURFEW / curlew’, it invites us to hear the bird’s liquid call as it plies its oracular flight down to the valley below. The transition of letters—inward folded ‘f’ for alert ‘l’—translates natural song into human alarm. As the evening shadows gather we slip into exile; the tocsin tolls and it is time we were safely home from the hill. Imaginatively we have entered Stonypath, Little Sparta, genius loci of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Further on we may wander into ‘a small grove composed of young pine trees and delicate columns. All the needles which fall from the trees are carefully swept into heaps around the foot of the columns.’ A poem in slate catches the branches’ outline and, as the breezes shush, we read another inscription: ‘WOOD / WIND / SONG, WIND / SONG / WOOD, WOOD- / WIND / SONG’. The poem belongs here because this is where the poet first heard the wind. Carved, the words suggest permanence; sun and shade, wind, birdsong, the transitory effects of nature, they too are integral to the garden poem.

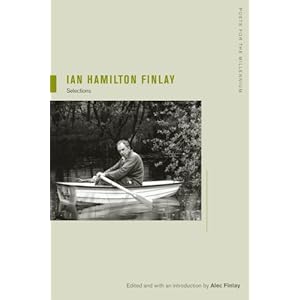

More than any other poet of the modern era, Finlay realized the potential of the poem as an object that belongs within an ‘environment’—though he would doubtlessly have preferred the term ‘garden’, ‘grove’ or ‘landscape’. To the adventurous he is an ‘AVANT-GARDEner’, pioneering poems in glass, aluminum and neon sited in parks and landscapes throughout the world. To the traditionalist his oeuvre is a belated recovery of Antique styles and age-old skills, eulogizing pastoral fishing-boats and wildflowers. Recent critical accounts conjure the garden as cynosure for a reclusive Neoclassical ‘genius’, whereas, for the poet, its status was elusive—inevitably so, given it was Stonypath, his fond home, and Little Sparta, his martial state, complete with stamps, medals, monuments, a flag and Garden Temple.

The poet’s remarkable letters reveal a lyric sensitivity and riven identity, for Finlay was a ‘makar’ whose expansive poetics arose from a homesickness that was life-defining, his vision shadowed by a profound sense of cosmological division: ‘The sum of my work is tragic. But it is centred on the lyrical; so much of it is pastoral, Virgilian.’ If readers wish, they can enter this poetic domain, even touch the text with their fingertips. Finlay belonged to that generation of innovators who grasped the means of poetic production. Embracing the text as a Platonic essence which must then be embodied—not in a voice projected, but as a thing placed, rooted even. Each poem carried the potential to assume different guises, through the careful choice of typeface, printed format or material; each word weighted or floated within its own space. For outdoor poems he devised composed landscapes. For indoor poems there were the myriad forms of typeface, card, print and book. These diverse settings are largely absent in this volume: the decision to adopt a uniform design style for Selections is supported by Finlay’s own preference for standardized collections, such as Honey by the Water (1972) and The Blue Sail (2002).

There was a constant interplay in Finlay’s imagination, between generic landscapes imbued with a painterly vision and magical encounters, such as those with the curlew, or the skylarks whose songs gave measure to family walks around the moor. I can still hear my father looking out the window, saying, ‘Sue—come and look at the light’. He briefly trained as an artist; after laying down his brushes, he remained a painter in outlook. His celebrated garden—born of a youthful dream of philosophers wandering a classical landscape—composed views which he ‘signed’ after his beloved painters, Claude, Poussin, Friedrich and Corot. His subtle response to place depended upon his painterly imagination; but, invited to create works of art for distant landscapes, he also depended on a particular gift for collaboration. Illness prevented him leaving home, and the work of scoping and installing was carried out by his wife, Sue, and latterly, by Pia Maria Simig. His poem-objects were created with gifted collaborators. He also collaborated intellectually with critics, most notably an ongoing dialogue with his preferred commentator, Stephen Bann.

Finlay began as an author of short stories and plays, yet he came to reject ‘secular’ prose, setting aside consecutive sentences in favour of the aphorism—which he likened to the philosopher’s ‘hand-grenade’. The inclusion here of a generous selection of his detached sentences allows the reader to enjoy the poems alongside their witty companions. His later poems were themselves frequently imaginative collaborations with the past, employing found text, bibliography and interpolation. These collaborative impulses and strategies were expansive. They arise from the poet’s contested relation to authority, a theme that can be traced back to the early Kafkaesque fable, ‘The Money’ (1954), where the artist, moved with an absolute sense of truth, resigns from society— a breach that would vigorously reassert itself in later disputes. The character of the artist in this story is a grown-up version of the children who appear in other stories and plays of the era: the wee boys who roam secret glens; the teenage girls walking the tide-line ‘like dancers—like on a tightrope’; each set apart from the world of adult authority.

Later he would sacrifice such symbolic characters: ‘I wanted to revive an old tradition, of poets, philosophers, artists, craftsmen, working together, towards a common aim, with good will [. . .] I set out to make works which bore no trace of the personality of Ian Hamilton Finlay (though that, of course, as I also know, is what has made them immediately identifiable as Finlay’s, in another way)’. Sharing the authority of poesis, he believed that the gap between two people was a generative space into which the muses slipped. Declaring his garden retreat ‘an attack’, the ‘Jacobin’ Finlay confronted contemporary culture with the higher authority of the classical tradition. Inscribing a domain in which the poet-philosopher could once again hold sway, his fictional children grew into the young revolutionary Saint-Just, interrogating liberal democracy with taboo imagery of power.

These principles were actualized in a series of disputes or ‘wars’, as Finlay reacted fiercely to hostile critical judgments or threats to his garden republic. Fury urged him on, and, in a paean to creativity, he confessed that, for him, art sprang from a thunderous intensity of feeling: ‘what I get in certain moments is a really wild excitement about my work and a feeling of “fantastic”, if some great clash of ideologies is occurring, or when I conceive of a new kind of work. It’s those kind of moments on a tightrope that are extraordinary. I don’t know, it’s like being on the peak of two searchlights that have crossed and the feeling it’s not really you but you’re carrying this thing along.’ The glare of these twin beams would in time draw him to eras of historical tragedy, the Third Reich and the French Revolution, which he replayed as myth and allegory.

The vertiginous shifts of form and subject-matter—early plays, stories and poems, lyrical portraits of the Scottish Highlands; non-didactic Concrete poems of the 1960s; garden poetry of the 1970s; didactic revolutionary poems from his armed domain in the 1980s; the late return to the pastoral of the 1990s—can only be grasped in terms of the drama of the poet’s life. For all his rejection of psychologism and disapproval of biography, Finlay self-dramatised his anomie to an extraordinary degree. Conflict is inherent to his psyche: it cannot be reconciled, must not be pacified. Some critics have concealed his intimate life and glossed over his engagement with power, estranging the work from tensions the poet insisted upon. His quarrels began as variants on that longstanding Scottish literary tradition, the ‘flyting’, but he chose to translate his later disputes—some sought, others imposed—into the ‘clash of ideologies’, ‘wars’, exposing tensions he was determined our age should confront.

Finlay was the greatest Scottish writer of letters since Robert Louis Stevenson; letters were his favourite emblem of friendship, his primary method of working with collaborators, and his weapon of choice. Extracts from his vital, warm, sometimes stormy correspondence are stitched together here so the reader can follow his ideas as they evolve, and compare them with the thoughtful residue of his sentences. Finlay’s maxims amuse and provoke. His ‘Table Talk’ has vim and tang, and his passionate belief in the spiritual role of culture and the non-commercial potential of art continue to resonate. Some attitudes will be judged contrarian: however we negotiate his politics, much is forgiven by the charm of Domestic Pensées (2004) and the touching ‘Detached Sentences on Exile’ (1983), which so clearly reveal the origins of his rage in feelings of homesickness. Finally the reader has the necessary material to hand with which to illuminate the ‘tightrope’ Finlay trod, between animus and sensitivity; traumatized relation to the social world and commitment to friendship; fragility before wild nature and devotion to the garden. In his later years he liked to say that he was not a poet at all, but a ‘revolutionary’: Selections reinstates the truly radical nature of Finlay’s project, for his output is a diverse and generous index of poetic potential, and this remains his most revolutionary achievement.

Finlay’s enactment of a poetics stilled in stone, subject to the flux of nature, was intimately connected in his imagination with the harmony of oppositions, as an early letter to Ernst Jandl makes clear: ‘I have never sorted a garden before and it is very fascinating—it certainly gives one a very clear idea of impermanency, and of the power of time, grass, and weeds, the fragility, and beauty, of order.’ His commitment to the landscape garden tradition would coincide with his discovery of Heraclitus—a philosopher whom Finlay acclaimed as the father of the thunderbolt, warring elements and form, as if to show his distaste for flux. Despite the Enlightenment tenor of the gardener-poet’s discourse with history and philosophy, his engagement with language remained divinatory. From the moment he settled at Stonypath, the act of naming rediscovered its fundamental importance. It is the principle which illuminates his one-word poems, found poems, adapted alphabets, poetic fragments, anagrams as well as the minimal operations enacted in IDYLLS (1987). Naming is by turns division, divination and revelation; the poet a harbinger, revealing concealed meanings, hidden relationships, bound oppositions.

We may struggle to follow the Heraclitean Finlay over the years that followed, as the Virgilian lemon-shaped fishing-boat gives way to the sublime mountain-ravine guillotine, but the rhyme of meaning resounds implacably. The great adventure of the garden refined these generative procedures in a way no other contemporary poet had achieved: it remains the decisive chiasma in his poetics, leading eventually—and in his mind, inevitably—to his dedication of the entire domain to the poetic muses, as 'Little Sparta.'

No comments:

Post a Comment