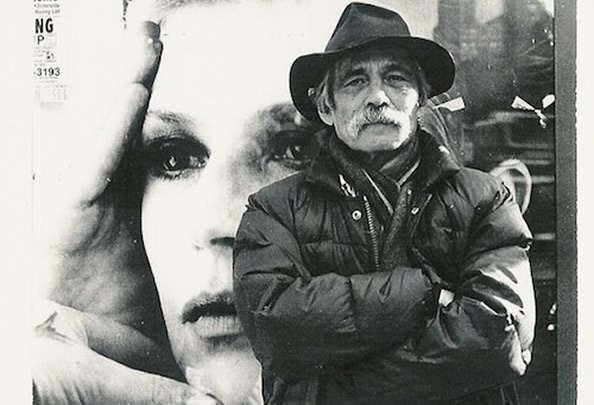

[In an effort to rescue poems & poets from the last

century who may otherwise be lost in the rush & crush of time, I will be

reposting a number of works originally published only in the blogger version of

Poems and Poetics. The intent of these excerpts from Frank Kuenstler’s oeuvre

was to celebrate the publication in 2011 of his posthumous book The Enormous Chorus (Pressed Wafer, Boston),

by posting Michael O’Brien’s Introduction and two of Kuenstler’s poems. In praise of Kuenstler and his work I wrote

the following: “The retrieval

here of a fair portion of Frank Kuenstler’s prolific work is an event of the

utmost importance toward the mapping of a true history of American poetry in the

second half of the twentieth century. It

is also a delight to see & to read so much of it now & to marvel, as I

did for the small part of it I knew from before, at the brilliant flights (of

‘fancy’ I would like to say) between different worlds & levels of

discourse. Others have tried & some

have succeeded, but none with more grace & élan than what he shows here.” The

Enormous Chorus can still be ordered in paper from Small

Press Distribution. (J.R.)]

BLIND OSSIAN ADDRESSES THE SUN AGAIN

A day

of snow on the Riviera, the burlesque queens

are

mermaids, simple as the moon. Another New Year’s

Day

in Havana, without discourse, they who cultivated

the

dimensions of their bodies, like lizards

are

regimented as our shadows. That’s bad news,

The

natural gambler opined. A traveller on the steps of Odessa

in distress & the going is hard &

slow,

Enormous snowflakes stripped as the voice

you know.

I should really be writing a letter to

everybody

saying

what I mean. I mean the bodies are blonde, brown

as

sunshine, while my feet are cold. There is no news

in the world for us, only images grasped at,

or fed us

like straws. The possible dimensions are

what remind

Us

that we were born once upon a time, & yelled like dawn.

The gamblers have moved south to oil

& coffee country.

The television sets up north transmit

pictures.

Snow is socialized. A rumor persists

that estimates of the life of the sun have

been wildly exaggerated.

In the thirties it was Egypt & the other

Alexandria

You

cannot know.

I will walk in the snow & get my feet

wet. I will go

to

the movies. I will hope. The bloody braille of the sun

is my

tongue. The king was executed just because he thought

he could be happy. He enjoyed his job. He

enjoyed

having his friends around. He enjoyed having

money.

He

enjoyed Marilyn Monroe, if such a thing was possible.

Degree by degree I went blind, thinking of

the sun in Havana,

thinking its eye was as narrow & wide as

a pair of hips.

I

will walk in Autumn. The Eiffel Tower will greet me, tell

me in Turkish the way to Afghanistan.

Apollinaire & Vergil

will guide me, because I am blind, the

way to the Far East

dimension of the world’s highway, O South

The way musicians named Ossian have

always been led by clarinets

&

apprentice butchers since the world was young.

THE ENORMOUS CHORUS

&

nobody alive knows no more what love is supposed to mean

because

poets are engineers of the soul who build machines

for

living; & anthology succeeds anthology as the night the

night;

& the Cockney movie had no subtitles; & the banana

cake

was delivered with tea leaves in it, reminiscent of tong

wars,

from New Jersey, baked by a chicken-sexer; & still

they

tell me, “Say ‘Garden State’”, & I say, “Garden State”;

&

the Princeton tiger came like Christ the kite, in September;

&

TS Eliot read his poetry to a packed house; I mean auditorium;

&

the best modern furniture is designed by architects;

&

Jack Smith is gonna die of happiness; & there’ll be peace

in

Viet Nam & we’ll all be beautiful again (the typewriter

will

write a poem entitled “Manufacture”, or “War & Peace”

just

for the poet & his friend); & the coin will stop spinning

&

all the plays will be witty & largely beautiful; actresses

will

acquiesce in their diction; & the gangster movie will be

produced,

shot on location in Kansas, directed by a Frenchman;

the

‘new wave’ will roll to a dead halt on a black & white

highway;

successful tycoons will burn all their paintings,

like

nihilists, or Rouault, each in his Golden Pavilion; & the

lunch

waiters will run the country, having taken over the newspapers;

&

Grace Kelly & Robt. Kelly will tour paradise & Heaven,

remark

Billie Holiday teaching Robt. Young how to play Daddy

&

the saxophone; & Michelet will give us a worthy cosmology;

&

the FBI will invent a twittering machine that works; &

there

goes Richie Schmidt all dressed up, looking like a priest

INTRODUCTION

(by

Michael O’Brien)

Frank

Kuenstler’s “Canto 33” opens

In medias res, the human

voice, crystal,

making

a kind of rubric: three propositions at the outset of something said, or,

better,

Duke Ellington laying out the terms of a song. In

medias res comes from

Horace:

“in the midst of the thing,” the place where we begin a story, a day, between a

beginning we can’t remember and the end which is an end to all remembering. Here. Now. In what Wallace Stevens calls “The

the.” And what we find, in all this immediacy, this perpetual ongoing middle,

is the human voice. The poems show a constant appetite for

it, for engaging with its unbroken rivers of talk. And that voice is crystal:

“clear as crystal,” as we say, but also “a structure consisting of periodically

repeated, identically constructed congruent unit cells.” (This sounds like a

description of Lens, his first, most radical book.) To

crystallize is “to take on definite and permanent form.” Granted the way his

mind worked, crystal is also probably not far from a crystal set, a radio

housing voices, nor from Stendhal’s On Love, in

which crystallization is the process of an emotion finding its form. A lot of work for seven words, and with a

rhyme as well. But consider the associative processes that run these poems,

their density of reference, the swiftness of their transitions. The internet

works like this, all interacting simultaneities. And the glue that holds it all

together is human speech:

The world hangs by a

thread of verbs & nouns.

The

poems’ openness to the overtones of words is unfailing, sometimes to the

exclusion

of their everyday workhorse lives. The point was to find a way to bring

that

abundance to bear in the moment of the poem. Many poets proceed by cutting out

the overload; he tried to make room for it. He didn’t write as if English were

in a museum, and he didn’t write to put it there. Poetry was, by its nature, provisional;

that’s why he wrote so much of it. He was steadily intelligent but not at all

high-minded; if puns were good enough for Joyce, they were good enough for him.

Likewise gobbledygook—“trying to talk to Mama,” as he once described it. He was

discerning without prejudice: junk had its uses—cartoons, cheesy movies, newspaper

headlines. To move between the sublime and the ridiculous, as he did,

programmatically, all the time, and with great rapidity, wasn’t a blunder—they were

parts of the same terrain. He never treated his materials with superiority, though

often with compounded ironies. There is great sadness and anger in some of the

poems, and sometimes a blank opacity more troubling than either. But,

inexhaustibly, there is something like joy at the level of language.

Sometimes

he says it into being:

If summer is the image

of a string of pearls

There is music

everywhere.

where

assertion does the work of discovery. Other times the world is not posited

but

simply, or not so simply, given as found. For his findings were seldom simple.

Simplicity

surprised him, as it surprises us when it turns up in the poems.

One

mustn’t leave out how funny they are, how much pleasure they give, how

responsive

their quickness—“Who runs may read.” At their best, as, say, in “Blind

Ossian

Addresses the Sun Again,” their reach is immense. Over and over inchoate

feelings

take shape, change, move on. Fixity is rare in them, something stale and

lifeless.

It often seems as if he were doing six things at once, changing trains and

levels

of thought as he speaks: more than one person is talking, and all at once.

Precarious

to negotiate such a Babel.

The stakes of the poems were very high: to

come

to some kind of terms with the rich, rolling chaos of the world, make something

commensurate with it. What they do is this:

Praise what was ordered

a second in the mind

*

Hard

to make a selection of the poems of someone whose every impulse was for

inclusion.

Much remains to be done. A reprint of Lens—for

the book defies editing—is the next thing needed. Then manuscripts need to be

looked at—this selection draws only on the books that he published. The

Rabbi Kyoto Poems should be gathered and published, and The

Baseball Book, meant to secure his old age. Friends should be consulted: sometimes the

post office was his publisher. He was abundant.

There

is good news: tapes of two of his readings can be found at PennSound

(http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Kuenstler.html),

likewise five of the films, restored by Anthology Film Archives; his last two

books, In Which and The Seafarer, B.Q.E.,

and Other Poems, are available from Cairn Editions (jcfmob@verizon.net). But time passes. When

Lady Murasaki is asked by the Prince why she writes she says So

there will never be a time when people don’t know these things happened. His work

should not be lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment