1/

2/

The system of not-finishing-a-sentence became more and more

prevalent in the course of years, the more the souls lacked their own thoughts.

In particular, for years single conjunctions or adverbs have been spoken into

my nerves thousands of times; those ought only to introduce clauses, but it is

left to my nerves to complete them in a manner satisfactory to a thinking mind.

Thus for years I have heard daily in hundred-fold repetition incoherent words

spoken into my nerves without any context, such as “Why not?,” “Why, if,” “Why,

because I,” “Be it,” “With respect to him,” (that is to say that something or

other has to be thought or said with respect to myself), further an absolutely

senseless “Oh” thrown into my nerves; finally, certain fragments of sentences

which were earlier on expressed completely; as for instance

1. “Now I shall,”

2. You were too,”3. “I shall,”

4. “It will be,”

5. “This of course was,”

6. “Lacking now is,”

etc. In order to give the reader some idea of the original

meaning of these incomplete phrases I will add the way they used to be

completed, but are not omitted and left to be completed by my nerves. The

phrases ought to have been:

1. Now I shall resign myself to being stupid;

2. You were to be represented as denying God, as given to

voluptuous excesses, etc.;

3. I shall have to think about that first;

4. It will be done now, the joint of pork;

5. This of course was too much from the soul’s point of

view;6. Lacking now is only the leading idea, that is – we, the rays, have no thou

The infringement of the freedom of human thinking or more

correctly thinking nothing, which constitutes the essence of compulsive

thinking, became more unbearable in the course of years with the slowing down

of the talk of the voices, This is connected with the increased

soul-voluptuousness of my body and — despite all writing-down — with the great

shortage of speech-materials at the disposal of the rays with which to bridge

the vast distances separating the stars, where they are suspended, from my

body.

No one who has not personally experienced these phenomena

like I have can have any idea of the extent to which speech has slowed down. To

say “But naturally” is spoken B.b.b.u.u.u.t.t.t.

n.n.n.a.a.a.t.t.t.u.u.u.r.r.r.a.a.a.l.l.l.l.l.l.y.y.y. or “Why do you not then

shit?” W.w.w.h.h.h.y.y.y. d.d.d.o.o.o………….; and each requires perhaps thirty to

sixty seconds to be completed. This would be bound to cause such nervous

impatience in every human being not like myself more and more inventive in

using methods of defense, as to make him jump out of his skin …

Translation from

German by Ida McAlpine and Richard A Hunter

COMMENTARY

with John Bloomberg-Rissman

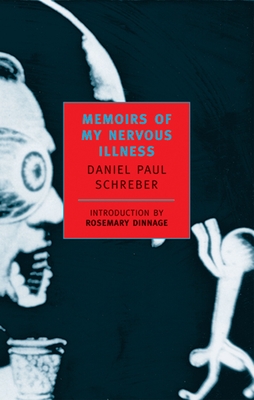

(1) “In November 1893, Daniel

Paul Schreber, recently named presiding judge of the Saxon Supreme Court, was on

the verge of a psychotic breakdown and entered a Leipzig psychiatric clinic. He

would spend the rest of the nineteenth century in mental institutions. Once

released, he published his Memoirs

of My Nervous Illness (1903), a harrowing account of real and delusional

persecution, political intrigue, and states of sexual ecstasy as God's private

concubine. Freud's famous case study of Schreber elevated

the Memoirs into the most important psychiatric textbook of paranoia

… Schreber's text becomes legible as a sort of

‘nerve bible’ of fin-de-siècle preoccupations and obsessions,

an archive of the very phantasms that would, after the traumas of war,

revolution, and the end of empire … cross the threshold of modernity into a

pervasive atmosphere of crisis and uncertainty … [It is possible to argue] that

Schreber's delusional system--his own private Germany--actually prefigured the

totalitarian solution to this defining structural crisis of modernity … [and to

show] how this tragic figure succeeded in avoiding the totalitarian temptation

by way of his own series of perverse identifications, above all with women and

Jews.” (Eric L Santner, My Own Private

Germany: Daniel Paul Schreber’s Secret History of Modernity)

(2) It is not hard to see Schreber’s encounter

with voices & rays & so forth as a crisis

of humanist reading. On some level, he seems to have experienced modernist

art practice avant la lettre, with a

kind of awareness of just how threatening that would be to the humanist

project. One could also argue that he not only experienced modernism, he also

experienced what came to be called postmodernism & what Jeffrey T. Nealon

calls its present “post-postmodern intensification”

(Post-Postmodernism or, The Cultural

Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism). In which case it seems possible to

understand Schreber’s memoirs as a kind of reading of a less & less

familiar, more & more threatening world, which continues to resonate. And the innovative strategies with language, as presented

here, bring it still more surely into our present mix.

No comments:

Post a Comment